Music Educators Association of New Jersey

Serving teachers and students since 1927

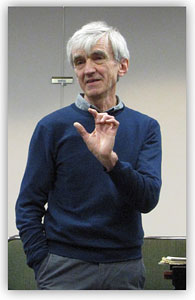

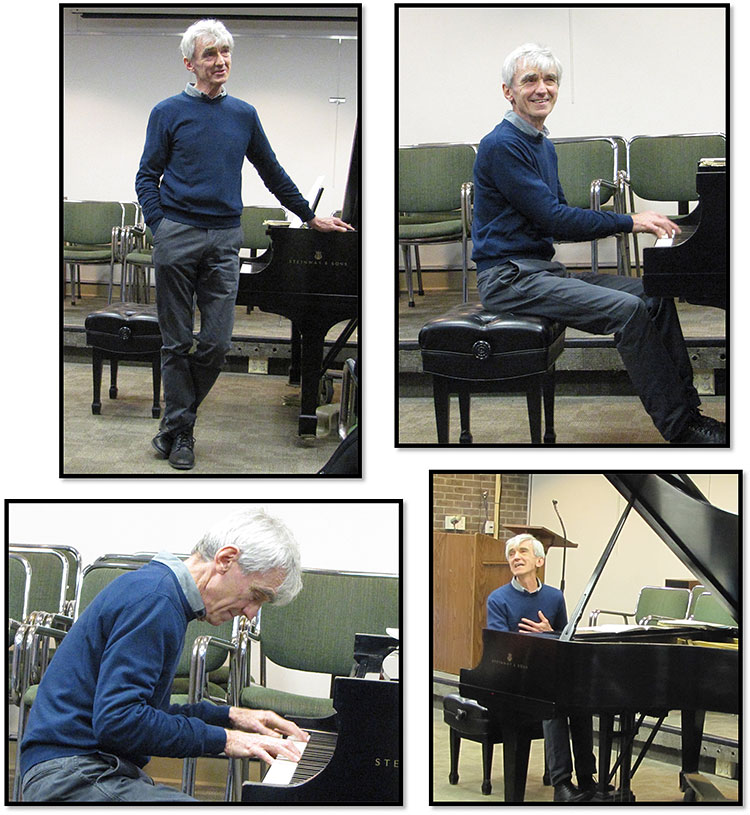

Paul Roberts, an expert on Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, presented an insightful discussion and wonderful performances of selections from Debussy’s “Children’s Corner“ and Préludes, Book I. Hostess Ruth Kotik introduced Mr. Roberts, an internationally known pianist, writer, lecturer, and teacher. His extensive résumé may be read here.

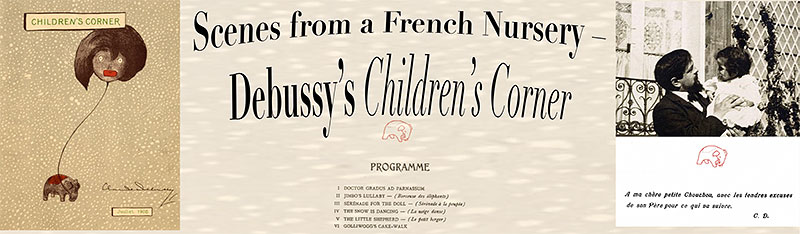

Mr. Roberts began with noting that Debussy designed the cover of the original Durand & fils edition of “Children’s Corner” with a drawing of Jimbo, the stuffed toy elephant perpetuated in the six piece set. Debussy lovingly dedicated “Children’s Corner” to his daughter, Chouchou. The collection reflects the interest in the psyche of children evoked by Sigmund Freud’s writings. Despite the English titles, (a nod to Chouchou’s English nanny), “Children’s Corner,” with its abounding good humor and wit, and use of French nursery tunes, is clearly French. One composition involves a special activity (keyboard exercises), another concerns an object (a child’s toy), a third is a genre piece (cakewalk, ragtime). “These are character pieces, apart from impressionism,“ Paul Roberts opined. They may seem simple, but they are “distilled simplicity.” Although studied by children, they are for adults, offering a view of a child’s world from an adult’s perspective. “The Snow is Dancing” might suggest a child looking at the snow from a window, or an adult recalling that childhood experience.

Mr. Roberts began with noting that Debussy designed the cover of the original Durand & fils edition of “Children’s Corner” with a drawing of Jimbo, the stuffed toy elephant perpetuated in the six piece set. Debussy lovingly dedicated “Children’s Corner” to his daughter, Chouchou. The collection reflects the interest in the psyche of children evoked by Sigmund Freud’s writings. Despite the English titles, (a nod to Chouchou’s English nanny), “Children’s Corner,” with its abounding good humor and wit, and use of French nursery tunes, is clearly French. One composition involves a special activity (keyboard exercises), another concerns an object (a child’s toy), a third is a genre piece (cakewalk, ragtime). “These are character pieces, apart from impressionism,“ Paul Roberts opined. They may seem simple, but they are “distilled simplicity.” Although studied by children, they are for adults, offering a view of a child’s world from an adult’s perspective. “The Snow is Dancing” might suggest a child looking at the snow from a window, or an adult recalling that childhood experience.

Paul Roberts then performed “Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum, “a prelude for fingers.” A study in C major, spiced with chromaticism, lively yet tender, it is the composer’s musical message to his daughter to practice. The piece begins with rapid notes in repeated patterns; the drill is interrupted by a retenu section; the exercise resumes, and the Très animé at m. 67 leads to an exuberant “show off” finish. We applauded!

Debussy created new sonorities and tonal colors with his innovative melodies and harmonies. We listen to his nontraditional music as differently as we would regard impressionistic painting compared to earlier art. To demonstrate this, Mr. Roberts played the opening chiming pentatonic chord passages of “La Cathédrale engloutie” (literally, The Engulfed Cathedral) and the beginning of Chopin’s Polonaise-Fantaisie, Op. 61, where a ground tone generates a series of notes. Chopin resolves harmonic dissonances but Debussy does not.

A performance and discussion of “Jimbo’s Lullaby” followed. Paul Roberts spoke of the witty yet touching musical portrayal of Jimbo, a stuffed toy elephant being lulled to sleep. “This is child music,” he remarked; it uses the pentatonic scale, the universal “music of innocence.” He asked, “How do you teach expression? How do you teach rubato? How do you follow the direction doux et un peu gauche (sweet and a bit clumsy)? To interpret these pieces, think about the character of the subject. Find clues implied in the score; make deductions, use your imagination.”

A performance and discussion of “Jimbo’s Lullaby” followed. Paul Roberts spoke of the witty yet touching musical portrayal of Jimbo, a stuffed toy elephant being lulled to sleep. “This is child music,” he remarked; it uses the pentatonic scale, the universal “music of innocence.” He asked, “How do you teach expression? How do you teach rubato? How do you follow the direction doux et un peu gauche (sweet and a bit clumsy)? To interpret these pieces, think about the character of the subject. Find clues implied in the score; make deductions, use your imagination.”

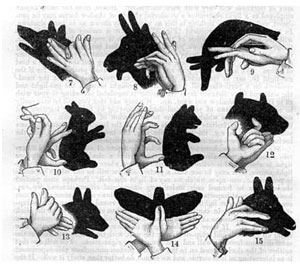

In a pre-cinema world, people attended “shadow plays”: shifting shadows cast onto a screen using hands, cutout designs, or other objects. Debussy had played an upright piano in the pit at these shows. “Jimbo’s Lullaby” is very cinematic, Paul Roberts claimed, and proceeded to play it while telling a story. The pentatonic melody begins appropriately in the bass. Then seconds are introduced, sounding rather tentative at first. Finally a pulse is established and the melody enters in the treble. The tempo picks up with the bass lumbering along on a repeated whole tone path in eighth notes (m.39). “It’s like the chase music in a shadow play,” we’re told. Finally, the music quiets down. The discussion and performance added to our understanding and appreciation of this frequently taught piece.

In a pre-cinema world, people attended “shadow plays”: shifting shadows cast onto a screen using hands, cutout designs, or other objects. Debussy had played an upright piano in the pit at these shows. “Jimbo’s Lullaby” is very cinematic, Paul Roberts claimed, and proceeded to play it while telling a story. The pentatonic melody begins appropriately in the bass. Then seconds are introduced, sounding rather tentative at first. Finally a pulse is established and the melody enters in the treble. The tempo picks up with the bass lumbering along on a repeated whole tone path in eighth notes (m.39). “It’s like the chase music in a shadow play,” we’re told. Finally, the music quiets down. The discussion and performance added to our understanding and appreciation of this frequently taught piece.

Our Debussy expert then returned to Préludes, Book I. Debussy’s inventiveness went beyond traditional composing practice. Mr. Roberts asked, “Where do the opening chords of “La Cathédrale engloutie” go? They just hang around.” To show Debussy’s departure from highly structured classicism, he played the beginning of Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata for comparison. Debussy opened up a new world without chord progression: harmonic stasis. Debussy also creates startling musical moments. “Think of the flickering brightness of silent films,” Paul Roberts suggested. Turning to “Minstrels,” he pointed out music mimicking picked guitar strings, drums, out of tune clarinets (using tone clusters), bluesy squeaking brass, and minstrel street band sounds. As he played, he told his own story inspired by the succession of musical elements in the piece.

Our Debussy expert then returned to Préludes, Book I. Debussy’s inventiveness went beyond traditional composing practice. Mr. Roberts asked, “Where do the opening chords of “La Cathédrale engloutie” go? They just hang around.” To show Debussy’s departure from highly structured classicism, he played the beginning of Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata for comparison. Debussy opened up a new world without chord progression: harmonic stasis. Debussy also creates startling musical moments. “Think of the flickering brightness of silent films,” Paul Roberts suggested. Turning to “Minstrels,” he pointed out music mimicking picked guitar strings, drums, out of tune clarinets (using tone clusters), bluesy squeaking brass, and minstrel street band sounds. As he played, he told his own story inspired by the succession of musical elements in the piece.

Mr. Roberts categorized “La serenade interrompue” (The Interrupted Serenade), as program music: music that tells a story. “Discover that story from the score and from the title." Finding meaning and nuance in the music, Mr. Roberts told us a story he derived as he played. The repeated notes, mm.5-10, suggest a guitar picking, and with picking throughout, it’s clearly a Spanish serenade! "Don’t pedal this guitar picking, but you may add pedal where strumming is suggested. The melodic middle section (the interrupted singer) has a Spanish or North African flavor; the rhythmic chord passages represent the interrupting minstrel band.”

Mr. Roberts categorized “La serenade interrompue” (The Interrupted Serenade), as program music: music that tells a story. “Discover that story from the score and from the title." Finding meaning and nuance in the music, Mr. Roberts told us a story he derived as he played. The repeated notes, mm.5-10, suggest a guitar picking, and with picking throughout, it’s clearly a Spanish serenade! "Don’t pedal this guitar picking, but you may add pedal where strumming is suggested. The melodic middle section (the interrupted singer) has a Spanish or North African flavor; the rhythmic chord passages represent the interrupting minstrel band.”

With no pedal notations, decisions are left to the performer. Remember that damper quarter-pedaling, half-pedaling, and flutter pedaling are essential techniques for this repertoire. Una corda pedal, and at times, sostenuto pedal may also be used.

Mr. Roberts played excerpts and briefly discussed “La puerta del vino,” (Préludes, Book II), and the three movements of “Estampes” (Prints). His interpretations were moving, his range of dynamics and his use of the pedal were amazing. He then launched into a discussion of the imagery in “La Cathédral engloutie” before treating us to a breathtaking performance. A brief question and answer period ended the program.

Bertha Mandel, writer

Nancy Modell, photos and page design

Ruth Kotik, Hostess