Music Educators Association of New Jersey

Serving teachers and students since 1927

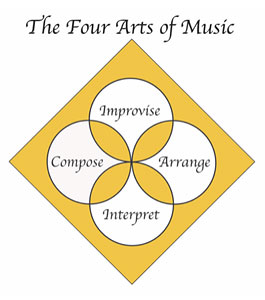

Forrest Kinney, pianist, arranger, composer, author, lecturer, and teacher, presented an engrossing program, "The Four Arts of Music: A New Paradigm for Music Education." Focusing on the teaching of arranging and improvisation, the presenter supported his talk with impressive demonstrations in which members of the MEA audience participated.

A principle central to Mr. Kinney's many works is that a truly complete musician is able to arrange, to improvise, to interpret, and to compose. All too often, traditional music lessons cultivate the art of interpretation to the neglect of the other three arts. Forrest Kinney's mission is to strengthen the abilities of musicians in these other skills. To achieve that goal, he has developed teaching techniques and presents them at his frequent lectures and in his many publications. His piano music books (published by Frederick Harris Music) are designed to aid a teacher in exploring these neglected creative areas. For more essential information please visit Forrest Kinney's website at forrestkinney.com.

Reflecting on keyboard music at the time of J.S. Bach, Mr. Kinney mentioned the keyboardist's skills in "realizing" a figured bass. For decades following, pianists were expected to be able to improvise. Variations, a form of arranging, were popular. To illustrate that point, Mr. Kinney charmed us with a variation of "Happy Birthday" in the style of Gershwin. Improvisation contests were common. Before the commerce of mass publishing, composers would write for their own needs, unless composing under commission. Concerts did not feature entire sonatas, but a collection of movements and other selections. Composers like Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, and Liszt would routinely render the first performance of their own works. They also taught. As the piano grew more popular as a solo instrument, and piano ownership became more widespread, musicians became more specialized. Composing, performing, arranging, and teaching became separate professions.

Aiming "to help others to be creative," Forrest Kinney strives to help teachers stimulate inventiveness in their students. He begins teaching the art of arranging with helping a student to play tunes "by ear." This is followed by adding a bass accompaniment of fifths, and ultimately, of triads. A beginner reader can progress to using a "lead sheet . . . akin to the old figured bass system." Finally, the three main elements of arranging are introduced:

Although his teaching techniques could be implemented at any level of instruction, Forrest cautioned teachers to be sensitive in their approach. A beginner might know the names of the keys but nothing more, so in that case, refrain from using any terminology that might be intimidating. Rather than standing next to a student in a dominant attitude, place two seats at the keyboard and invite your student to sit. Then, sit next to him/her. (The teacher operates the pedal.) Promote confidence.

Volunteer "students" from the audience participated. For each improvisation that followed, Forrest gave his "students" a framework or patterns to initiate the process. For example, he asked the student to play a dyad of a fifth in the bass on black keys and to repeat it at a steady pulse. Next came repositioning the hand at another set of fifths on black keys, as the teacher improvises in the treble, only on black keys. Next, the teacher plays the ground bass "pattern" while the student improvises above. Limiting the student's improvised melody to black keys is a simple way to get started.

Exotic sounding melodies were created by improvising based on keyboard topography and hand position: the pattern Persia involved placing fingers on the keys D - E Flat - F Sharp - G, and then, keeping that hand shape, shifting the hand to A - B Flat - C Sharp - D. The student uses the "pattern" to generate melodies in which repetitions, key order, and rhythms may be altered. Forrest Kinney also created variations in timbre by first placing a graphite pencil on the strings just above Middle C to produce a metallic rattle, and later placing a lightweight music book (Pattern Play) on the lower strings to create a dampened sound. The novel sounds stimulated our imagination. Another pattern, Blues on Black, uses a bass pattern of broken E Flat and A Flat seventh chords against a treble which inserts a very occasional A natural, the "blue" note. It's a process, but eventually, the student learns to play both bass and treble. A new improviser is born! It's the "duet to solo" plan.

The culminating improvisation was "Musical Chairs" for five: three seated at the keyboard, (a bass broken chord, a mid-range fifth and fourth pattern, and the highest at free play) and two standing at the ready. As the seated trio plays, the two standing players either reach out and interject a musical comment on the keyboard, or replace a seated player. The "pupils" became energized. A supportive and skilled teacher produced results!

Addressing "interpreters," Forrest Kinney stressed that there is room for more than one single interpretation of any piece. That becomes evident when comparing performances of a piece by different artists. To further motivate the interpreters among us, he remarked that when he prepares for a classical recital, he finds that using his scores as material for improvising and arranging helps to keep his concert interpretations fresh.

Following experiences with arranging and improvising, the next step would be composing, which is beyond the scope of this session. Earlier in the week, some MEA members had attended a special class, a "Mini-Intensive," conducted by Forrest Kinney. They shared our enthusiasm for Forrest Kinney and his innovative ideas and practices.

Photos and layout, Nancy Modell

Bertha Mandel, writer