Music Educators Association of New Jersey

Serving teachers and students since 1927

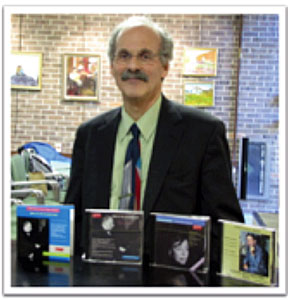

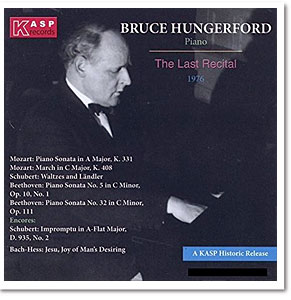

Donald Isler’s program on “Great and Underappreciated Pianists of the 20th Century: Adrian Aeschbacher, Constance Keene and Bruce Hungerford” reflected his personal connections with these artists. He included excerpts of their recordings on the KASP label, a company Mr. Isler founded.

Learn more about Mr. Isler’s multifaceted musical career (classical pianist, piano teacher, pianist adjudicator, recording artist and founder of KASP Records) at http://www.kasprecords.com/donaldisler.htm. KASP recordings have been featured on David Dubal’s distinguished radio program, Reflections from the Keyboard. Mr. Isler currently serves as treasurer for the Associated Music Teachers League, Inc. His Facebook page, Isler’s Insights, includes personal experiences and interviews.

Learn more about Mr. Isler’s multifaceted musical career (classical pianist, piano teacher, pianist adjudicator, recording artist and founder of KASP Records) at http://www.kasprecords.com/donaldisler.htm. KASP recordings have been featured on David Dubal’s distinguished radio program, Reflections from the Keyboard. Mr. Isler currently serves as treasurer for the Associated Music Teachers League, Inc. His Facebook page, Isler’s Insights, includes personal experiences and interviews.

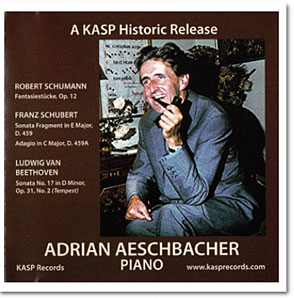

We were introduced to the artistry of the Swiss pianist Adrian Aeschbacher (1912-2002). He visited the United States once, in 1986, as adjudicator for the William Kapell Piano Competition, but toured extensively in Europe and South America and made many recordings. Adrian studied with his father, Carl Aeschbacher, a choral conductor, until age 17, and then worked with Emil Frey at the Zurich Conservatory. In 1932, he studied in Berlin with Artur Schnabel, lived with Donald Isler’s grandparents, practiced on their Bechstein grand, and taught their son, our speaker’s father. In 1938, the Isler family fled to the U.S. carrying the memories of this exceptional pianist.

Mr. Isler played Aeschbacher’s recording of Schumann’s Romance in B Flat Minor, Op. 28, No. 1, Sehr markiert. A singing melody projected well over an active broken chord bass. Donald Isler played a few measures from Romance in F Sharp Major, Op. 28, No. 2, Einfach, expressing another mood. It’s calm melody and slower tempo contrasted greatly with the fast pace and thick texture of the first piece. Aeschbacher was a master at playing music ranging from calm to passionate; he was an outstanding interpreter of Schumann and Schubert.

Mr. Isler played Aeschbacher’s recording of Schumann’s Romance in B Flat Minor, Op. 28, No. 1, Sehr markiert. A singing melody projected well over an active broken chord bass. Donald Isler played a few measures from Romance in F Sharp Major, Op. 28, No. 2, Einfach, expressing another mood. It’s calm melody and slower tempo contrasted greatly with the fast pace and thick texture of the first piece. Aeschbacher was a master at playing music ranging from calm to passionate; he was an outstanding interpreter of Schumann and Schubert.

We next heard Aeschbacher’s recording of Schumann’s Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6, I-VI. The dynamic scope and the shaping of phrases in the lively Lebhaft were excellent. The Innig (II) was truly heartfelt, very poignant, with a singing melody. Mit Humor (III) was cheerful with crisp solid chords and rhythmic playing. Ungeduldig (IV) moved impatiently along with a moving bass line pitted against a syncopated melody. Einfach was beautifully played with the top voice well projected above a discreetly played bass. Dynamics were simple, yet effective. After Sehr rasch (VI) with its driving tempo, clear articulation, and prudent use of pedal, we moved on.

We next heard Aeschbacher’s recording of Schumann’s Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6, I-VI. The dynamic scope and the shaping of phrases in the lively Lebhaft were excellent. The Innig (II) was truly heartfelt, very poignant, with a singing melody. Mit Humor (III) was cheerful with crisp solid chords and rhythmic playing. Ungeduldig (IV) moved impatiently along with a moving bass line pitted against a syncopated melody. Einfach was beautifully played with the top voice well projected above a discreetly played bass. Dynamics were simple, yet effective. After Sehr rasch (VI) with its driving tempo, clear articulation, and prudent use of pedal, we moved on.

Our next recorded treat was the Allegro moderato, the third of Schubert’s Moments Musicaux, D. 780. This was stunningly beautiful: wonderful tempo, tasteful use of pedal, beautiful shaping of phrases. One of our members exclaimed that she had never before heard it played so well. Many nodded in agreement.

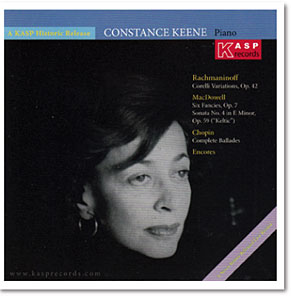

Next, we learned about Constance Keene, born in Brooklyn, (1921-2005), who made her debut at the age of ten, and a few years later began studying with Abram Chasins. Chasins would later collaborate with her as duopianists and become her husband. He was a student of Józef Hofmann. Keene won the 1943 Naumburg Piano Competition, and performed for the troops during the war. She was a sensation substituting for Horowitz in a recital. From 1969 to 2005, she taught at the Manhattan School of Music, conducting weekly master classes and accompanying students in concertos. Donald Isler studied with her from 1971-1975.

Among her outstanding recordings are works by Rachmaninoff, MacDowell, and Hummel. She continued to perform in later years, giving a concert in 1995 at the University of Houston that included Rachmaninoff’s Variations on a Theme of Corelli, some MacDowell and the Chopin Ballades. Donald Isler then played her recording of the Ballade No. 2, Op. 38. The opening bars were melodious; the Presto con fuoco sections were fast and exceedingly well articulated. We next heard the Keene recording of the frenetic Rush Hour in Hong Kong by Abram Chasins. It was an impeccable, clean performance.

Among her outstanding recordings are works by Rachmaninoff, MacDowell, and Hummel. She continued to perform in later years, giving a concert in 1995 at the University of Houston that included Rachmaninoff’s Variations on a Theme of Corelli, some MacDowell and the Chopin Ballades. Donald Isler then played her recording of the Ballade No. 2, Op. 38. The opening bars were melodious; the Presto con fuoco sections were fast and exceedingly well articulated. We next heard the Keene recording of the frenetic Rush Hour in Hong Kong by Abram Chasins. It was an impeccable, clean performance.

Finally, the focus fell on Australian pianist Bruce Hungerford (1922-1977), known as Leonard Hungerford until around 1958. Tragically, his short life ended in an automobile accident. In Australia, he was a student of Roy Shepherd, a former student of Alfred Cortot, before studying with Ignaz Friedman. In America, he studied with Carl Friedberg, a former student of Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms. In 1945, Hungerford lived in the International House in Morningside Heights while studying at Juilliard with Ernest Hutcheson and Olga Samaroff. The recording of some of Hungerford’s lessons with Carl Friedberg can be heard on the website of Arbiter Records (www.arbiterrecords.com). In the 1950s, Hungerford returned to Australia on tour, and later toured in East and West Germany, Belgium and England. He made no orchestral recordings in the States.

Finally, the focus fell on Australian pianist Bruce Hungerford (1922-1977), known as Leonard Hungerford until around 1958. Tragically, his short life ended in an automobile accident. In Australia, he was a student of Roy Shepherd, a former student of Alfred Cortot, before studying with Ignaz Friedman. In America, he studied with Carl Friedberg, a former student of Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms. In 1945, Hungerford lived in the International House in Morningside Heights while studying at Juilliard with Ernest Hutcheson and Olga Samaroff. The recording of some of Hungerford’s lessons with Carl Friedberg can be heard on the website of Arbiter Records (www.arbiterrecords.com). In the 1950s, Hungerford returned to Australia on tour, and later toured in East and West Germany, Belgium and England. He made no orchestral recordings in the States.

Don Isler described Hungerford as being “very spiritual.” As we listened to the recording of the Adagio After Marcello by Bach, we appreciated the very measured tempo, the pulsating chords, the resonant melody, and the sensitive treatment of each phrase.

As a teacher, Hungerford could be very generous, often letting lessons run over two hours, and accepting considerably less than his customary fee. He stressed acquiring a beautiful tone, and used verbal imagery (as did Friedberg). He advised, “You can use as much pedal as you want in Beethoven as long as no one knows you’re using the pedal!” He would remind students that Beethoven’s piano had less sustaining power than today’s instruments. On interpreting Chopin, Hungerford said rubato, lilt, and nuances of subtle rhythmic adjustments were essential.

Donald Isler demonstrated his own beautiful, rich tone by playing an excerpt from the Largo e mesto of Beethoven’s Sonata in D Major, Op. 10, No. 3, followed by his capricious playing of opening bars of the Scherzo from Beethoven’s Sonata in A Major, Op. 2, No. 2.

Finally, we were spellbound watching the DVD of Hungerford’s performance of the first movement of Beethoven’s Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58. Each phrase was perfectly shaped, the right hand sparkled against the Alberti bass, control of dynamics was steadfast, the scales were even, the trills (fingered 1323) topnotch. Donald Isler recommended Hungerford’s recordings of the Beethoven sonatas (Vanguard Records). He had attended some of these recording sessions.

Finally, we were spellbound watching the DVD of Hungerford’s performance of the first movement of Beethoven’s Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58. Each phrase was perfectly shaped, the right hand sparkled against the Alberti bass, control of dynamics was steadfast, the scales were even, the trills (fingered 1323) topnotch. Donald Isler recommended Hungerford’s recordings of the Beethoven sonatas (Vanguard Records). He had attended some of these recording sessions.

Thanks to Donald Isler, we now knew where we could explore archival records of these three and other underappreciated pianists. We could also appreciate the legacies of pianists as they were transmitted generation to generation. Kudos to Programs Chair Sophia Agranovich and her committee.

Bertha Mandel, writer

Nancy Modell, page design and photography