Music Educators Association of New Jersey

Serving teachers and students since 1927

Paul Roberts brought us into the intimacy of his London studio, drapes drawn closed and a soft light illuminating the music placed above his piano keyboard. He proceeded to enlighten us on the subject of Liszt and the Petrarch Sonnets, based on extensive research he had done while working on his book soon to be published: Reading Liszt: Words Becoming Music.

Paul has spent his career fascinated by the relationship between different art forms: Debussy and Impressionist paintings, Ravel and poetry, and our subject, Liszt’s three sonnets, inspired by three Petrarch poems. In his upcoming book, the chapter concerning Petrarch is titled: “The Music of Desire – The Three Sonnets of Petrarch.” Paul begins the chapter with the opening line from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night: “If music be the food of love, play on...”

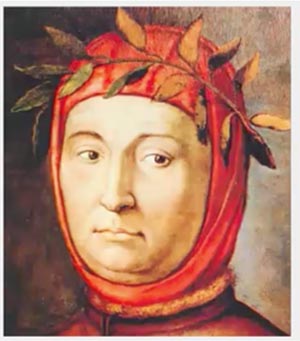

Love, in its many forms, is a constant theme from the time of the troubadours until our current days. Paul asks whether music by itself, without accompanying text, can express desire. Do we need words, as in a poem, in an opera, or a story? Paul draws a line across five centuries from Petrarch to Liszt. Petrarch (1304-1374) is considered the last troubadour – the first modern man. He was an extraordinary figure: a poet laureate who was awarded huge fame and prizes for his poetry, a fashionable diplomat and a devout man of letters celebrated for a large body of religious and philosophical writings in Latin. Petrarch wrote 366 poems in vernacular Italian, one for every day of the year. Those poems were addressed to the mysterious and unattainable Laura, with whom he was in love. She never returned his love. Thus, the poems are achingly beautiful, expressing the pain she causes him, how he loves, desires her and admires her beauty. She gradually becomes a spiritualized figure. In the first sonnet, when he first sees Laura, Petrarch writes, “Blessed be all the paper upon which I earned my fame.” He was going to be a great poet because of her. Unrequited love and fame are the abiding themes of the sonnets.

Love, in its many forms, is a constant theme from the time of the troubadours until our current days. Paul asks whether music by itself, without accompanying text, can express desire. Do we need words, as in a poem, in an opera, or a story? Paul draws a line across five centuries from Petrarch to Liszt. Petrarch (1304-1374) is considered the last troubadour – the first modern man. He was an extraordinary figure: a poet laureate who was awarded huge fame and prizes for his poetry, a fashionable diplomat and a devout man of letters celebrated for a large body of religious and philosophical writings in Latin. Petrarch wrote 366 poems in vernacular Italian, one for every day of the year. Those poems were addressed to the mysterious and unattainable Laura, with whom he was in love. She never returned his love. Thus, the poems are achingly beautiful, expressing the pain she causes him, how he loves, desires her and admires her beauty. She gradually becomes a spiritualized figure. In the first sonnet, when he first sees Laura, Petrarch writes, “Blessed be all the paper upon which I earned my fame.” He was going to be a great poet because of her. Unrequited love and fame are the abiding themes of the sonnets.

These ideas of fame and unrequited love are the connections to Liszt and become obvious in the 19th century, 500 years later. Liszt was a star of the 19th century. He was famous at age 18, and only became more so. As famous as a king, Liszt was generous, charismatic, played the piano like a god and women fell for him. So it is easy to see Liszt’s attraction to the poems, as he knows about fame, and has his muse on his arm. He lived in Italy for 18 months with his first great love, Countess Marie d'Agoult. There they absorbed the art of the Renaissance, felt the warm climate of Italy, and heard the sounds of the streets. This is where Liszt’s art, related to Petrarch’s, was born. Seeing Petrarch as a romantic would have been irresistible to Liszt, himself in the vanguard of the Romantic Period. Liszt would have read all the poems as a love story. For his contemporaries Victor Hugo and Honore Balzac, whom he knew well, Petrarch was all the rage. Hugo began one of his poems, “While I sleep, come close to where I lie, as Laura once appeared to Petrarch.” But Petrarch, with Laura representing a spiritual aspiration, could never name the physical desire. Hugo named that desire. Liszt reacted to the poems the way his contemporaries did.

The first sonnet describes the joy of a first meeting. Liszt sees each sonnet as a mode of theater - an introduction followed by a troubadour tellinga story. A 19th century curtain goes up, flamboyant in the way of nineteenth century Romanticism. The music begins with unresolved chords, soon resolved to settle us into our seats. The curtain rises on a 14th century scene. The left hand keeps the count while the melodic line is always off beat. This symbolizes the trouble in the center of the scene, constant heart palpitations which will lead to pain and hysteria in the second sonnet. A chromatic scale represents the poet’s tears, sadness and grief.

The first sonnet describes the joy of a first meeting. Liszt sees each sonnet as a mode of theater - an introduction followed by a troubadour tellinga story. A 19th century curtain goes up, flamboyant in the way of nineteenth century Romanticism. The music begins with unresolved chords, soon resolved to settle us into our seats. The curtain rises on a 14th century scene. The left hand keeps the count while the melodic line is always off beat. This symbolizes the trouble in the center of the scene, constant heart palpitations which will lead to pain and hysteria in the second sonnet. A chromatic scale represents the poet’s tears, sadness and grief.

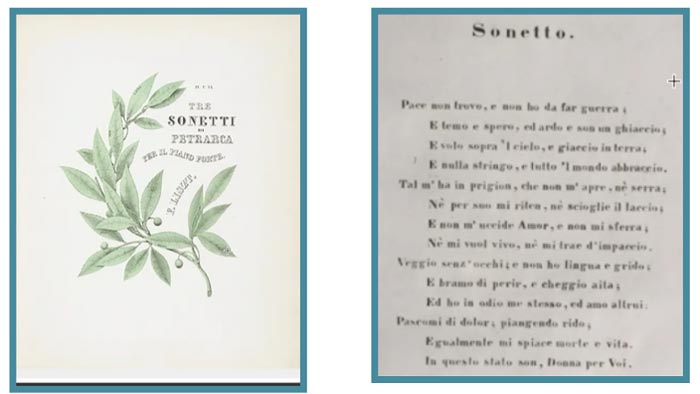

The second sonnet finds the poet in an outflow of passion and hysteria, tremendous oppositions: fire-ice, earth-sky, body-soul, freedom-imprisonment, you-I. (“Because of you, lady, I am this way,” states the last line of this sonnet.) The curtain goes up to the sound of chords more dissonant then in the first sonnet. In the first verse the sounds of flute, then guitar, then harpsichord are reflecting the “recitativo” markings in the score. The second verse includes successive “ritenuto-fermata” combinations. The melody, repeated notes that fall away, represents a shout, capturing tension and emotional charge. The melody is marked “forte,” and the accompaniment “piano.” This theme should not be played gently, like a nocturne. That interpretation would rob it of its tension. The same theme gets orchestrated to “fortissimo molto,” very passionate, hurried, “vibrato,” overt expressiveness. One has to apply maximum strength without beating the piano to death. (During a seven-year concert tour, Liszt played in large concert halls and adopted a big sound.)

When Liszt’s first edition of the sonnets was published, the poems were not published with them. As Liszt was adamant that the poems be published in front of the score, the second edition was made right: one can now read Petrarch’s poem before playing Liszt’s sonnet. The laurel branch represents the crown worn by Petrarch, as the poet laureate. “And his fame (laurel) grew with his love for Laura,” is written on the branch.

The third sonnet, in its original Italian, rhymes beautifully. (It is impossible to translate into English with rhymes.) Liszt makes the music rhyme by writing falling thirds throughout the piece. They are not monotonous, but rather they are an integral part of the natural flow of the melodic line. This poem speaks to Laura in death. (She died of the plague in the middle of the fourteenth century.) Her presence in heaven causes mountains to stop moving, streams to stop flowing, and leaves to stop rustling. Liszt captures “the sweet music drifting on the air.” With his unresolved harmonies, Liszt foreshadows late 19th century Impressionism.

He starts with rocking triplets, symbolizing heavenly bells, sky and sun. He then captures Laura ascending into heaven through unresolved chords - a whole page of remarkable cadential figures rising slightly in pitch with no downbeat. After the downbeat there is a sense of breathing, lifting. Most remarkably, in writing the music, Liszt responds to the language in the poems - a language he had to teach himself.

Paul’s playing of the three sonnets from Liszt's Années de pèlerinage was breathtakingly beautiful. We are lucky to have been treated to this performance.

To end his presentation, Paul shared with us a performance of Luciano Pavarotti singing the first sonnet with a piano accompaniment. Pavarotti is holding a handkerchief, his facial expressions reflective of the words sung. As he looks intensely into the distance, his acting continues, even when he is not singing.

Paul comments that, in contrast, a pianist lives the music internally, not externally. He believes that musicians can learn to inhabit a role the way actors do.

Yudit Terry, writer

Joan Bujacich, layout