Music Educators Association of New Jersey

Serving teachers and students since 1927

Using an analytical approach, Noa Kageyama, Ph.D. presented some of his strategies for performance success. Dr. Kageyama, a conservatory-trained violinist with degrees from Oberlin and Juilliard, is a performance psychologist on the Juilliard faculty and the performance psychology coach for the New World Symphony in Miami.

While attending the Juilliard Precollege, Noa observed that he played some truly good performances, but also had bad days, memory slips, catastrophic moments on stage, i.e., sub-par performances. His teacher says these things are caused by nerves and tells him to practice consistently, eat bananas, drink chamomile tea, take supplements. The subject of "performance psychology" never came up.

While attending the Juilliard Precollege, Noa observed that he played some truly good performances, but also had bad days, memory slips, catastrophic moments on stage, i.e., sub-par performances. His teacher says these things are caused by nerves and tells him to practice consistently, eat bananas, drink chamomile tea, take supplements. The subject of "performance psychology" never came up.

Sports psychology was an eye-opener. How to perform better under pressure? Athletes get mental preparation. Could similar preparation help musicians?

Noa noted two goals: (1) help a student to be a better pianist, and (2) help a student to play better in competition. There is a difference between: Practice plus performance, and Practice plus practice.

Mental Skills Training

Malcolm Gladwell's book Outliers: The Story of Success discussed the early stages of walking. When we start thinking about walking, we can't walk normally. Noa ran a short film showing a cat that overthought a leap and then could not complete the leap successfully. We need to recognize what it feels like when we do a successful movement.

HAVE PRE-PERFORMANCE ROUTINES. 1) Have a clear intention of exactly where you want the piece to go; have a target in mind. Do not think about what you don't want to have happen. Do not speak or think negatively. 2) Be more focused on an auditory sound. Produce the sound you want; your inner ear has to hear what you want to hear before you play.

BREATHE DIAPHRAGMATICALLY - SLOWER, DEEPER, CALMER "BELLY BREATHING." Put one hand on your chest, one on your stomach. Let your stomach expand. Try "tripoding" - sit down, lean over, elbows on thighs, feel your breath expanding. Focus on deep, slow, diaphragmatic breathing. Focus on exhaling first. Calm yourself down when you need to.

SCAN FOR TENSION. Remember what an easy breath feels like. At first take a lot of time - 15-20 seconds to compose yourself. Make it a consistent process, practice it over and over. Sit comfortably, eyes closed. Start taking in breath through nose, exhale through mouth. Focus on the sound of your breath. Pay attention to how inhaling and exhaling feels. Inhaled air feels cooler, exhaled air feels drier. Scan your body for tension. Feel and release tension in mouth, jaw, neck, shoulder, back, even be aware of tension in the hip and knees. Continue to think about the opening of a phrase. Remember how it feels when that opening of a phrase is effortless. See if your mind is clearer and quieter.

GET CENTERED. Do 5 or 6 repetitions of the below.

If you are shaky at the start of a piece, decide should you place your hands on the keys or not? The tactile sensation works for some people. Imagine a chord not actually there. Test this beginning in a practice room. Remember how you played the opening... fluid, flowing, think of a color, "cue up" that feeling. It may be a different process for every movement or piece. Do not focus on details.

Other suggestions:

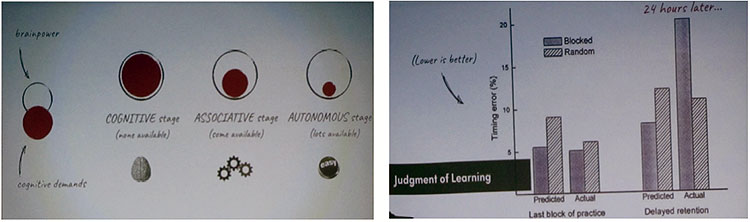

Constant versus Variable Practice

Blocked

15 min. on piece A

15 min. on piece B

15 min. on piece C

The blocked practicing was better at first

Random Practice

5 min. on A, 5 min. on B, 5 min. on C

5 min. on C, 5 min. on A, 5 min. on B

5 min. on B, 5 min. on C, 5 min. on A

Due to more practice in remembering, random practice was more stable in the long-term.

The random group had to work harder. Cause yourself to forget, then to remember. Then, when more experienced with a piece, do the shorter segment practicing.

Practice for success in performance, not just success in practice:

The way you play at home may need to change for a different piano or in different acoustics. You may need to modify your motor skills. Imagine you are in a huge competition. Put on a mock audition: Add subtle nuances, phrasing, and articulation. You can invent variations in the practice room so you do better on stage. Imagine your brain on improv, like a jazz pianist. The "As If" Game. If you have students who may get paralyzed with too many choices (options) or over pacing, ask them to emulate three favorite performers: play a piece as if they were Rubinstein, Argerich, or Kissin, using each performer's phrasing, sound, dynamic contrasts. Try playing like someone else for variety.

Playing the “As If” Game are MEA members Cherwyn Ambuter, Joan Bujacich, and Ruth Kotik.

It is challenging to guide a student where to keep his/her mind when performing. Set the metronome at the wrong tempo...challenge the student's concentration.

For further information, one may download "Strategies for Audition and Performance Success - A Workbook for Musicians" by Don Greene; read 10-Minute Toughness: The Mental Training Program for Winning Before the Game Begins by Jason Selk; consult Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III and Mark A. McDaniel; or explore Dr. Kageyama's website bulletproofmusician.com.

MEA members were enthusiastic about Dr. Kageyama's lecture and requested more of the same.

Beverly Shea, Hostess and writer

Nancy Modell, photographs and layout