Music Educators Association of New Jersey

Serving teachers and students since 1927

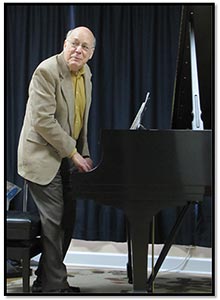

Victor Rosenbaum, renowned performer and pedagogue, began his analysis of how to approach classical music with a personal anecdote.

At a Master Class for talented high school students, a student played the Adagio movement of Mozart's Sonata in F (K332) dryly and rigidly. Victor, the facilitator that day, demonstrated how it could be played, using rubato, adding pedal and making the melody sing expressively like an opera singer might do. Amazed, the student said, "I didn't know you could do that in classical music!"

Victor proceeded to make a basic point. As teachers, we must question what the music should sound like -- not the style of the composer, rather the character of a particular piece itself. Put all the "rules" and preconceptions aside. Music and art should not be viewed as a series of restrictions; approach them as promising and potential explorations: What is possible? Where does the music lead you? Let the music be your guide and lead you to appropriate choices.

Victor proceeded to make a basic point. As teachers, we must question what the music should sound like -- not the style of the composer, rather the character of a particular piece itself. Put all the "rules" and preconceptions aside. Music and art should not be viewed as a series of restrictions; approach them as promising and potential explorations: What is possible? Where does the music lead you? Let the music be your guide and lead you to appropriate choices.

In the Mozart, the harmonies in this B flat movement change twice every measure. This greatly influences the melody, rhythm, and pulse. Some harmonies have great tension, some have points of relaxation; unexpected changes affect the timing, intensity and musical character. In the very first measure, for example, an expressive moment occurs after the ornamental "turn", when one note - the E natural - changes the harmony and makes all the difference. Linger over it. Enjoy it. Be responsive to the contour of the melody, paying special attention to the large (more expressive) intervals, appoggiaturas, stressed passing tones and pitches outside the tonality. Awareness of the texture (is it homophonic, polyphonic, thick, thin?) and register also helps foster understanding of the expressive nature and color of a piece. They affect the balance of voices and pedaling as well.

Rhythm is a major contributor to the character of a piece. Responding to rhythmic gestures will go a long way toward establishing an appropriate "style." The pulse - not the beat - but what the harmony suggests as the rate of change, is an important organizing factor that helps the listener make sense of the music. Music is, after all, organized sound. Encourage students to relate to the large pulse; then they can use rubato and still be in time. So much of music is not notate-able. Elasticity is simply not possible to notate. We can indicate ritardandos and accelerandos, but we must use our own judgment as to how they are played.

Rhythm is a major contributor to the character of a piece. Responding to rhythmic gestures will go a long way toward establishing an appropriate "style." The pulse - not the beat - but what the harmony suggests as the rate of change, is an important organizing factor that helps the listener make sense of the music. Music is, after all, organized sound. Encourage students to relate to the large pulse; then they can use rubato and still be in time. So much of music is not notate-able. Elasticity is simply not possible to notate. We can indicate ritardandos and accelerandos, but we must use our own judgment as to how they are played.

Much "Classical" music is written in paired measures - stressed measures followed by resolution. In 4 bars, 1 and 3 are strong; 2 and 4 are lighter. Sensitivity to the hierarchy relative to the weight of the phrase is important in sorting out the phrasing. Did Mozart know he was a "classical" composer? He certainly knew the aesthetic of his day and knew his music was different from the contrapuntal style of the Baroque. Did he intentionally make his different? Perhaps.

Great composers have a wide emotional vocabulary. They create incredible musical moments. They break the rules. In fact, most of the rules came after the music was composed, created by theorists and musicologists attempting to codify something from the past. While the intention is valid, the results tend to put musical styles in a box with rigid guidelines. Certain composers are associated with certain genres, but Victor Rosenbaum encourages all teachers to teach music appreciation. Teach the amazing things about music. Teach the sound of the piece rather than the assumed sound of the composer. The minor section of the Mozart Adagio movement is so moving and heart-wrenching that it possibly served as a beautiful model for Chopin; it is so emotionally satisfying. Do we think of Mozart as a romantic composer? Bach, Haydn, Beethoven and Schubert, composers from different musical eras, all wrote very dramatic sonatas in C minor. Compare them. Explore each one's uniqueness. Make the music live!

Great composers have a wide emotional vocabulary. They create incredible musical moments. They break the rules. In fact, most of the rules came after the music was composed, created by theorists and musicologists attempting to codify something from the past. While the intention is valid, the results tend to put musical styles in a box with rigid guidelines. Certain composers are associated with certain genres, but Victor Rosenbaum encourages all teachers to teach music appreciation. Teach the amazing things about music. Teach the sound of the piece rather than the assumed sound of the composer. The minor section of the Mozart Adagio movement is so moving and heart-wrenching that it possibly served as a beautiful model for Chopin; it is so emotionally satisfying. Do we think of Mozart as a romantic composer? Bach, Haydn, Beethoven and Schubert, composers from different musical eras, all wrote very dramatic sonatas in C minor. Compare them. Explore each one's uniqueness. Make the music live!

In summary, Mr. Rosenbaum said, "Keep your 'I' on the music." Your Intellect and Intuition, combined, lead to Insight, which sparks Imagination (what is the music saying?), which results in Inspiration (feeling inspired about a particular piece).

"INSPIRED PLAYING - BASED ON

INTELLECT, INTUITION, INSIGHT AND IMAGINATION

IS ALWAYS 'IN STYLE!'"

About Victor Rosenbaum:

About Victor Rosenbaum:

Former chair of the New England Conservatory piano department for more than 10 years, Victor Rosenbaum served on the faculty of the Eastman School of Music and Brandeis University, as chair of piano at the Eastern Music Festival, and as Director/President of the Longy School of Music. He has performed widely as soloist and chamber music performer in the U.S., Europe, Asia, Israel and Russia, in such prestigious venues as Alice Tully Hall (NYC) and the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, Russia. He has collaborated with such artists as Leonard Rose, Arnold Steinhardt, Robert Mann, and the Cleveland and Brentano String Quartets, among others. Festival appearances have included Tanglewood, Rockport, Yellow Barn, Kneisel Hall, Kfar Blum (Israel) and Musicorda, where he is on the faculty. He has been soloist with the Indianapolis and Atlanta symphonies and the Boston Pops. An accomplished composer and conductor, Mr. Rosenbaum also gives master classes and lectures worldwide. His highly praised recording of Schubert is on Bridge Records.

B.A., cum laude, Brandeis University; M.F.A., Princeton University. Piano with Leonard Shure, Rosina Lhevinne; theory and composition with Martin Boykan, Edward T. Cone, Earl Kim, Roger Sessions.

Written by Charlene Step

Photography and layout, Nancy Modell

Hostess, Tomoko Harada